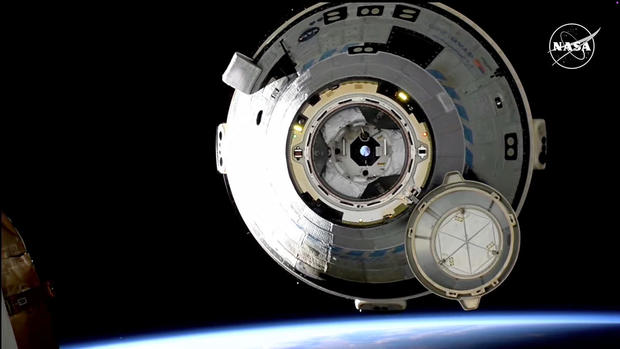

Leaving its crew behind in orbit, Boeing’s troubled Starliner spacecraft undocked from the International Space Station Friday and chalked up a successful unpiloted return to Earth, closing out a disappointing test flight with an on-target New Mexico touchdown.

Despite NASA’s concerns about earlier thruster problems and multiple helium leaks in the ship’s propulsion pressurization system, the Starliner had no problems undocking and moving away from the station at 6:04 p.m. EDT and executing a critical 59-second deorbit braking maneuver at 11:17 p.m. to drop out of orbit.

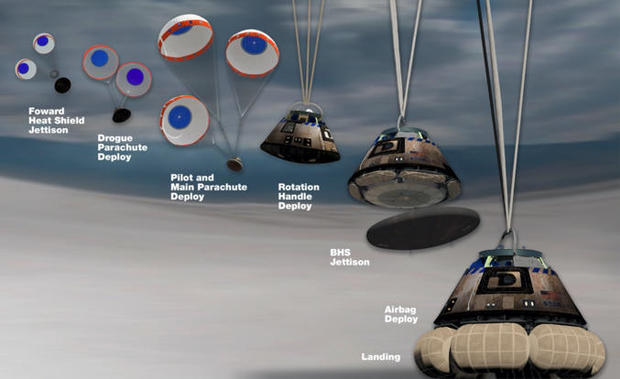

Slamming into the discernible atmosphere 400,000 feet above the Pacific Ocean, the Starliner streaked across the Baja Peninsula and northern Mexico before descending to a parachute-and-airbag assisted touchdown at White Sands Space Harbor in the New Mexico desert at 12:01 a.m. EDT Saturday.

NASA and Boeing recovery teams stationed nearby quickly reached the spacecraft to begin “safing” operations and to carry out post-landing inspections.

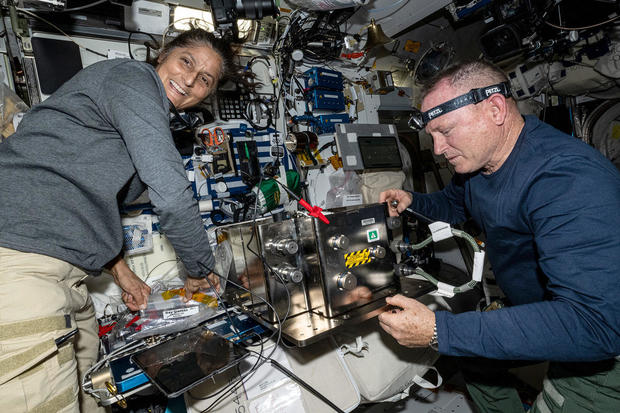

Left behind in orbit were Starliner commander Barry “Butch” Wilmore and pilot Sunita Williams, who were ordered to remain aboard the space station after NASA managers decided their spacecraft could not be trusted to bring them safely back to Earth.

As it turned out, the Starliner appeared to perform well. The known helium leaks did not get worse and the reaction control system thrusters in the ship’s service module, the ones that had problems early in the mission, worked as required to safely move the spacecraft away from the station and to keep it stable during the de-orbit burn.

But the road ahead is far from clear for the Boeing ferry ship. The service module was jettisoned as planned before re-entry, burning up in the atmosphere, and engineers will not be able to examine the hardware to pin down exactly what caused the helium leaks and degraded thruster performance during the ship’s rendezvous with the station.

Instead, they will face more data analysis, tests and potential redesigns expected to delay the next flight, with or without astronauts aboard, to late next year at the earliest.

“Even though it was necessary to return the spacecraft uncrewed, NASA and Boeing learned an incredible amount about Starliner in the most extreme environment possible,” Ken Bowersox, space operations director at NASA Headquarters, said in a statement.

“NASA looks forward to our continued work with the Boeing team to proceed toward certification of Starliner for crew rotation missions to the space station,” Bowersox added.

In any case, the successful landing was a shot in the arm for Boeing engineers and managers, who insisted the Starliner could have safely brought Wilmore and Williams back to Earth. Steve Stich, manager of NASA’s commercial crew program, agreed that if the crew had been on board “it would have been a safe, successful landing.”

“From a human perspective, all of us feel happy about the successful landing,” he said during a post-landing news conference. “But then there’s a piece of us, all of us, that we wish it would have been the way we had planned it. We had planned to have the mission land with Butch and Suni on board.”

He denied a rift with Boeing, but said “I think there (are), depending on who you are on the team, different emotions associated with that. I think it’s going to take a little time to work through that, for me a little bit and then for everybody else on the Boeing and NASA team.”

Including the astronauts. Wilmore and Williams now will remain aboard the space station until late February, hitching a ride home aboard a SpaceX Crew Dragon spacecraft being readied for launch Sept. 24 to ferry the next long-duration crew to the lab.

The Crew Dragon normally launches with four crew members, but two NASA astronauts were bumped from the upcoming Crew 9 flight to free up seats for Wilmore and Williams. They’ll join Crew 9 commander Nick Hague and Russian cosmonaut Alexander Gorbunov for a normal six-month tour of duty.

By the time they return to Earth around Feb. 22, Wilmore and Williams, who originally expected to spend about eight days in orbit, will have logged more than eight-and-a-half months in space.

NASA astronaut Frank Rubio faced a similar dilemma in 2022 when his six-month stay aboard the station was extended to more than a full year because of problems with the Russian Soyuz spacecraft that carried him to orbit.

“I think going from six months to 12 months is tough, but it’s not as tough as going from eight days to eight months,” Rubio said in an interview with CBS News. Asked how Wilmore and Williams took the news of their extension, he said “they’re doing great.”

“Certainly, there’s a little part of you that’s disappointed,” he added. “It’s okay to acknowledge that. But you also can’t mope around for the entire time, right? … You just have to kind of dedicate and rededicate yourself to the mission.”

Series of setbacks for Boeing

The decision to bring the Starliner down without its crew was a morale-sapping blow to Boeing in the wake of earlier problems that delayed the Starliner’s first piloted flight by nearly four years, required a second unpiloted test flight and cost the company more than $1.5 billion above and beyond its NASA fixed-price contract.

The Starliner woes come on top of Boeing’s ongoing struggle to restore public confidence in the wake of two 737 Max 8 airliner crashes, a close call with an Alaska Airlines 737 flight that suffered a door plug blowout earlier this year and more recent problems with an upgraded version of the company’s long-haul 777 aircraft.

It’s not yet known what will be needed to correct the problems encountered on the latest Starliner flight, whether another costly test flight will be required or when the ship might be ready for active service ferrying astronauts to and from the station.

“I want to recognize the work the Starliner teams did to ensure a successful and safe undocking, deorbit, re-entry and landing,” Mark Nappi, Boeing’s Starliner program manager said in a statement. “We will review the data and determine the next steps for the program.”

The space station crew closed the Starliner’s hatch at 1:29 p.m. Thursday. The day before, as Williams worked inside the Starliner helping arrange return items to ensure the right balance and center of gravity, she described the moment as “bittersweet.”

“Thanks for backing us up, thanks for looking over our shoulder and making sure we’ve got everything in the right place,” she told flight controllers. “We want her to have a nice, soft landing in the desert.”

After a final check of the weather at the New Mexico landing site, hooks in the Starliner’s docking mechanism disengaged, allowing springs on the station side to push the uncrewed ferry ship away.

A series of thruster firings then were executed to slowly push the spacecraft out in front of the lab complex before looping up and over the top and departing to the rear. Seven minutes after undocking, the Starliner exited a 1,300-foot-wide safety zone known as the “keep out sphere.”

Given the earlier thruster problems, NASA shortened the departure timeline to get the Starliner well away from the station as quickly as possible. Sixteen minutes after leaving the keep-out sphere, the spacecraft exited the larger “approach ellipsoid,” another safety zone around the ISS that measures 2.5 miles long and 1.2 miles wide. The thrusters worked flawlessly throughout the early stages of the departure.

The ship’s flight computers were programmed to guide the spacecraft toward a precise point in space for the critical de-orbit braking burn needed to drop the ship out of orbit. On cue, four large orbital maneuvering and attitude control rockets — OMACs — fired for 59 seconds, slowing the ship’s 17,100-mph velocity by nearly 300 mph. That was just enough to drop the far side of the orbit into the atmosphere for re-entry and descent to the New Mexico landing site.

While the powerful OMAC braking rockets were firing, smaller reaction control system, or RCS, jets fired on computer command to keep the Starliner stable and pointed in the right direction.

Once the de-orbit burn was complete, the Starliner’s service module, housing the OMACs, 28 RCS jets, the helium tanks and other critical but no-longer-needed systems, was jettisoned to burn up on the atmosphere.

The crew module, protected by a heat shield and equipped with 12 RCS jets of its own, then began its re-entry at an altitude of about 400,000 feet, enduring temperatures as high as 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit as it plunged back into the discernible atmosphere at nearly five miles per second.

The southwest-to-northeast re-entry trajectory carried the Starliner across the Baja Peninsula, the Gulf of California, northern Mexico and into New Mexico.

At an altitude of about 24,500 feet, two small drogue parachutes unfurled, slowing and stabilizing the Starliner. About one minute later, at an altitude of 8,000 feet, three pilot parachutes pulled out the ship’s three 104-foot-wide main parachutes, slowing the decent to about 18 mph.

At an altitude of 2,500 feet, airbags inflated to reduce landing impact forces to the equivalent of walking speed. Touchdown came at 12:01 a.m. EDT (10:01 p.m. Friday local time).

The de-orbit burn and computer-orchestrated attitude control system firings were crucial to getting out of orbit on the precise trajectory needed for a pinpoint landing. And all of those firings required pressurized helium to push propellants to healthy thrusters.

During the Starliner’s rendezvous with the space station on June 6, the day after launch, five RCS jets were “deselected” by the flight computer because of degraded thrust. In addition, four helium leaks in the propulsion pressurization system were detected, adding to a small leak that was detected before launch.

After extensive tests and analyses, Boeing engineers concluded the helium leaks were the result of slightly degraded seals exposed to toxic propellants over an extended period. But even with the leaks, they said the Starliner had 10 times more helium on board than needed to get out of orbit.

The thruster problem, testing indicated, was caused by high temperatures that, in turn, caused internal Teflon seals to deform in poppet valves, restricting the flow of fuel.

The high temperatures, the engineers concluded, were largely the result of manual flight control tests that caused the jets to fire hundreds of times in rapid-fire fashion while the craft was oriented so those same jets were in direct sunlight for an extended period.

In test firings later in the mission the jets appeared to be working normally, indicating the seals had contracted back to, or near, their original shape.

Boeing argued manual flight tests would be ruled out for a piloted return to Earth, the craft would be oriented to minimize solar heating on the suspect jets and fewer firings would be needed in the absence of a rendezvous.

Boeing tried to convince their counterparts at NASA that the Starliner had plenty of margin and could bring Wilmore and Williams safely back to Earth.

But NASA managers did not accept Boeing’s “flight rationale” and opted to bring the Starliner down without its crew.

“Spaceflight is hard. The margins are thin. The space environment is not forgiving,” said Norm Knight, director of flight operations at the Johnson Space Center. “And we have to be right.”