After weeks of debate, NASA has ruled out bringing two astronauts back to Earth aboard Boeing’s Starliner capsule because of lingering concerns about multiple helium leaks and degraded thrusters, both critical to a successful re-entry, officials said Saturday.

Despite successful tests of the Starliner’s maneuvering thrusters, detailed analyses and confirmation the known propulsion system helium leaks are stable and have not worsened, NASA concluded there is no way to prove the systems will continue to operate normally, ensuring a safe de-orbit, re-entry and landing.

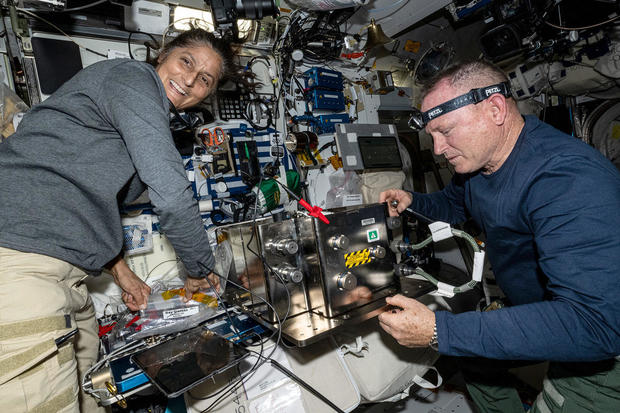

The decision means two of four “Crew 9” astronauts scheduled for launch to the International Space Station aboard a SpaceX Crew Dragon on Sept. 24 will give up their seats so Starliner commander Barry “Butch” Wilmore and co-pilot Sunita Williams can come home in their place next February.

“NASA has decided that Butch and Suni will return with Crew 9 next February and that Starliner will return uncrewed,” NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said at a post-readiness review news conference on Saturday. “I want you to know that Boeing has worked very hard with NASA to get the necessary data to make this decision.”

He continued: “We want to further understand the root causes (of the earlier problems) and understand the design improvements so that the Boeing Starliner will serve as an important part of our assured crew access to the ISS.”

Nelson said new Boeing CEO Kelly Ortberg assured him the company remains committed to the Starliner program, which NASA is relying on to provide independent access to the space station alongside SpaceX.

“I told him how well Boeing worked with our team to come to this decision, and he expressed to me an intention that they will continue to work the problems once Starliner is back safely and that we have our (assured) crew access to the space station,” Nelson said.

Launched June 5, Wilmore and Williams originally expected to spend a little more than a week in space in the Starliner’s first piloted test flight. They’ll now spend at least 262 days in orbit — nearly nine months — before returning to Earth around Feb. 22 with the two Crew 9 fliers after they wrap up a normal six-month tour of duty.

In the process, Wilmore and Williams will become the first astronauts in history to fly in space aboard four different spacecraft: NASA’s space shuttle, Russia’s Soyuz, Boeing’s Starliner and SpaceX’s Crew Dragon.

The Starliner, meanwhile, will be commanded to undock from the space station’s forward port as early as Sept. 6 and carry out an unpiloted re-entry and touchdown at White Sands, New Mexico, to bring the long-awaited test flight to a disappointing conclusion.

With the Starliner’s departure, only the four-seat Crew 8 capsule, which arrived at the lab last March, will be available to serve as a lifeboat if an emergency forces its four-member crew, along with Wilmore and Williams, to evacuate before the Crew 9 ferry ship arrives.

While the odds of an evacuation are remote, SpaceX will work with NASA and the station crew to rig makeshift seats in the Crew 8 Dragon before the Starliner’s undocking to accommodate Wilmore and Williams in an emergency.

Once the Crew 9 capsule docks, the four outgoing Crew 8 fliers, wrapping up their own six-month expedition, will reconfigure their ship for a normal undocking and return to Earth around Oct. 1 as planned. Wilmore and Williams will remain behind aboard the station with the two Crew 9 fliers launching Sept. 24.

The decision ruling out a piloted Starliner return was a crushing blow to Boeing in the wake of earlier problems that delayed the Starliner’s first piloted flight by nearly four years, required a second unpiloted test flight and cost the company more than $1.5 billion above and beyond its NASA fixed-price contract.

The Starliner woes come on top of Boeing’s ongoing struggle to reassure the public in the wake of two 737 Max 8 airliner crashes, a close call with an Alaska Airlines 737 flight earlier this year and more recent problems with an upgraded version of the company’s long-haul 777 aircraft that have shaken confidence in the aerospace giant.

But from NASA’s perspective, Nelson said he had faith in Boeing, the prime contractor of the International Space Station and the agency’s Space Launch System moon rocket, calling the contractor “a great partner for NASA over the years.”

When the Starliner was launched on June 5, one small helium leak in the Starliner’s propulsion system was known, but it was not considered a safety threat. During rendezvous with the space station the day after launch, four more leaks developed and five of the ship’s aft-facing thrusters did not operate as expected.

Those two issues triggered two months of extensive testing and analysis, adding another $125 million to the mission’s price tag, according to a Boeing financial update.

Boeing adamantly argued that tests and analyses of the helium leaks and initial trouble with maneuvering thrusters showed the spacecraft had more than enough margin to bring Wilmore and Williams safely back to Earth.

The helium leaks are understood, Boeing said, they have not gotten worse and more than enough of the pressurized gas is on board to push propellants to the thrusters needed to maneuver and stabilize the spacecraft through the critical de-orbit braking burn to drop out of orbit for re-entry and landing.

Likewise, Boeing engineers believe they understand what caused a handful of aft-facing maneuvering jets to overheat and fire at lower-than-expected thrust during rendezvous with the space station, causing the Starliner’s flight computer to shut them down during approach.

Ground tests of a new Starliner thruster, fired hundreds of times under conditions that mimicked what those aboard the spacecraft experienced, replicated the overheating signature, which was likely caused by multiple firings during tests of the capsule’s manual control system during extended exposure to direct sunlight.

The higher-than-expected heating likely caused small seals in thruster valve “poppets” to deform and expand, the analysis indicates, which reduced the flow of propellant. The thrusters aboard the Starliner were test-fired in space under more normal conditions and all operated properly, indicating the seals had returned to a less intrusive shape.

But there was no way to guarantee the seals would not deform again during thruster firings after undocking or during the de-orbit “burn” when larger rocket motors would generate high temperatures in pods housing the smaller thrusters, which are needed to maintain the spacecraft’s stability for a precisely targeted landing.

“We’re all committed to the mission, which is to bring Butch and Suni back,” said Steve Stich, NASA’s commercial crew program manager. “But as we got more and more data over the summer and understood the uncertainty of that data, it became very clear to us that the best course of action was to return Starliner uncrewed.

“If we had a way to accurately predict what the thrusters would do all the way through the deorbit burn and through the separation sequence, I think we would have taken a different course of action. But when we looked at the data and looked at the potential for thruster failures with a crew on board … it was just too much risk”.

Boeing did not participate in the Saturday news briefing. In a statement following the announcement, Boeing said the company “continues to focus, first and foremost, on the safety of the crew and spacecraft. We are executing the mission as determined by NASA, and we are preparing the spacecraft for a safe and successful uncrewed return.”

In the wake of the space shuttle’s retirement, NASA awarded two Commercial Crew Program fixed-price contracts in 2014, one to SpaceX valued at $2.6 billion and the other to Boeing for $4.2 billion.

The goal was to end NASA’s post-shuttle reliance on Russia’s Soyuz and to resume launching American astronauts from U.S. soil aboard American rockets and spacecraft. Equally important to NASA: having two independent spacecraft for crew flights to the ISS in case one company’s ferry ship runs into problems that might ground it for an extended period.

“We’re one launch anomaly from losing our ability to support this amazing thing that we do on the International Space Station,” said Nick Hague, one of the four Crew 9 astronauts. “We’re trying to develop Starliner to be that redundant system.” A recent Falcon 9 upper stage failure “underscores why we need redundancy more than anything I can think of.”

The original target date for initial piloted commercial crew flights was 2017. Funding shortfalls in Congress and technical snags delayed development, including an explosion during a ground test that destroyed a SpaceX Crew Dragon.

But the California rocket builder still managed to kick off piloted flights in May 2020, successfully launching two NASA astronauts on a Crew Dragon test flight to the space station.

Since then, SpaceX has launched eight operational crew rotation flights to the station, three research missions to the lab funded by Houston-based Axiom Space and a purely commercial, two-man, two-woman trip to low-Earth orbit paid for by billionaire pilot and businessman Jared Isaacman.

Isaacman and three different crewmates are scheduled to blast off Tuesday on another commercial SpaceX flight — Polaris Dawn — to set a new Earth-orbit altitude record and to carry out the first commercial spacewalks.

Going into that flight, 50 people have flown to orbit on 13 Crew Dragon flights. Boeing has now launched two astronauts — Wilmore and Williams — but it’s not yet known when the ship will be ready to fly again or even if yet another test flight will be ordered.

During an initial unpiloted test flight in December 2019, unexpected software and communications glitches prevented a planned rendezvous with the space station. Boeing corrected those problems and opted to carry out a second uncrewed test flight, at its own expense.

But during the second countdown, engineers ran into problems with stuck propulsion system valves in the Starliner’s service module. Engineers eventually traced the problem to moisture intrusion and corrosion, triggering another lengthy delay.

The second Starliner test flight in May 2022 was a success, docking at the space station as planned and returning to Earth with a pinpoint landing. But in the wake of the flight, engineers discovered fresh problems: possible trouble with parachute harness connectors and concern about protective tape wrapped around wiring that could catch fire in a short circuit.

Work to correct those issues pushed the first crewed flight to this year. When all was said and done, Boeing spent more than $1.5 billion of its own money to pay for the additional test flight and corrective actions.